Customize the admin form

By registering the

Question model with

admin.site.register(Question),

Django was able to construct a default form representation. Often, you’ll want

to customize how the admin form looks and works. You’ll do this by telling

Django the options you want when you register the object.

Let’s see how this works by reordering the fields on the edit form. Replace

the

admin.site.register(Question) line with:

polls/admin.py

from django.contrib import admin

from .models import Question

class QuestionAdmin(admin.ModelAdmin):

fields = ['pub_date', 'question_text']

admin.site.register(Question, QuestionAdmin)

You’ll follow this pattern – create a model admin class, then pass it as the

second argument to

admin.site.register() – any time you need to change the

admin options for a model.

This particular change above makes the “Publication date” come before the

“Question” field:

This isn’t impressive with only two fields, but for admin forms with dozens

of fields, choosing an intuitive order is an important usability detail.

And speaking of forms with dozens of fields, you might want to split the form

up into fieldsets:

polls/admin.py

from django.contrib import admin

from .models import Question

class QuestionAdmin(admin.ModelAdmin):

fieldsets = [

(None, {'fields': ['question_text']}),

('Date information', {'fields': ['pub_date']}),

]

admin.site.register(Question, QuestionAdmin)

The first element of each tuple in

fieldsets is the title of the fieldset.

Here’s what our form looks like now:

Adding related objects

OK, we have our Question admin page, but a

Question has multiple

Choices, and the admin page doesn’t display choices.

Yet.

There are two ways to solve this problem. The first is to register

Choice

with the admin just as we did with

Question. That’s easy:

polls/admin.py

from django.contrib import admin

from .models import Choice, Question

# ...

admin.site.register(Choice)

Now “Choices” is an available option in the Django admin. The “Add choice” form

looks like this:

In that form, the “Question” field is a select box containing every question in the

database. Django knows that a

ForeignKey should be

represented in the admin as a

<select> box. In our case, only one question

exists at this point.

Also note the “Add Another” link next to “Question.” Every object with a

ForeignKey relationship to another gets this for free. When you click “Add

Another”, you’ll get a popup window with the “Add question” form. If you add a question

in that window and click “Save”, Django will save the question to the database and

dynamically add it as the selected choice on the “Add choice” form you’re

looking at.

But, really, this is an inefficient way of adding

Choice objects to the system.

It’d be better if you could add a bunch of Choices directly when you create the

Question object. Let’s make that happen.

Remove the

register() call for the

Choice model. Then, edit the

Question

registration code to read:

polls/admin.py

from django.contrib import admin

from .models import Choice, Question

class ChoiceInline(admin.StackedInline):

model = Choice

extra = 3

class QuestionAdmin(admin.ModelAdmin):

fieldsets = [

(None, {'fields': ['question_text']}),

('Date information', {'fields': ['pub_date'], 'classes': ['collapse']}),

]

inlines = [ChoiceInline]

admin.site.register(Question, QuestionAdmin)

This tells Django: “

Choice objects are edited on the

Question admin page. By

default, provide enough fields for 3 choices.”

Load the “Add question” page to see how that looks:

It works like this: There are three slots for related Choices – as specified

by

extra – and each time you come back to the “Change” page for an

already-created object, you get another three extra slots.

At the end of the three current slots you will find an “Add another Choice”

link. If you click on it, a new slot will be added. If you want to remove the

added slot, you can click on the X to the top right of the added slot. Note

that you can’t remove the original three slots. This image shows an added slot:

One small problem, though. It takes a lot of screen space to display all the

fields for entering related

Choice objects. For that reason, Django offers a

tabular way of displaying inline related objects; you just need to change

the

ChoiceInline declaration to read:

polls/admin.py

class ChoiceInline(admin.TabularInline):

#...

With that

TabularInline (instead of

StackedInline), the

related objects are displayed in a more compact, table-based format:

Note that there is an extra “Delete?” column that allows removing rows added

using the “Add Another Choice” button and rows that have already been saved.

Customize the admin change list

Now that the Question admin page is looking good, let’s make some tweaks to the

“change list” page – the one that displays all the questions in the system.

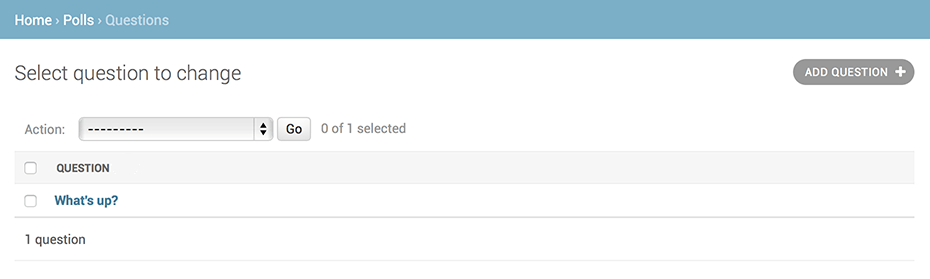

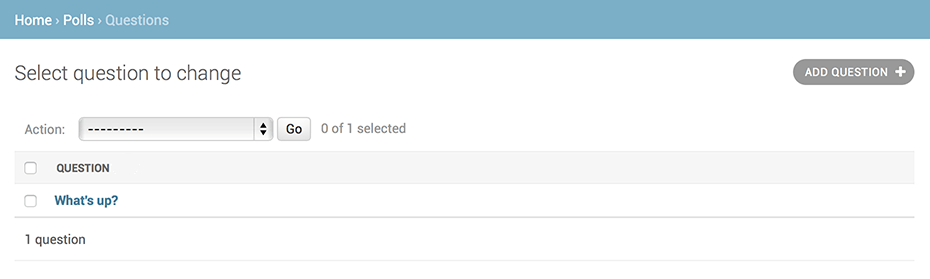

Here’s what it looks like at this point:

By default, Django displays the

str() of each object. But sometimes it’d be

more helpful if we could display individual fields. To do that, use the

list_display admin option, which is a

tuple of field names to display, as columns, on the change list page for the

object:

polls/admin.py

class QuestionAdmin(admin.ModelAdmin):

# ...

list_display = ('question_text', 'pub_date')

Just for good measure, let’s also include the

was_published_recently()

method from

Tutorial 2:

polls/admin.py

class QuestionAdmin(admin.ModelAdmin):

# ...

list_display = ('question_text', 'pub_date', 'was_published_recently')

Now the question change list page looks like this:

You can click on the column headers to sort by those values – except in the

case of the

was_published_recently header, because sorting by the output

of an arbitrary method is not supported. Also note that the column header for

was_published_recently is, by default, the name of the method (with

underscores replaced with spaces), and that each line contains the string

representation of the output.

You can improve that by giving that method (in

polls/models.py) a few

attributes, as follows:

polls/models.py

class Question(models.Model):

# ...

def was_published_recently(self):

now = timezone.now()

return now - datetime.timedelta(days=1) <= self.pub_date <= now

was_published_recently.admin_order_field = 'pub_date'

was_published_recently.boolean = True

was_published_recently.short_description = 'Published recently?'

For more information on these method properties, see

list_display.

Edit your

polls/admin.py file again and add an improvement to the

Question change list page: filters using the

list_filter. Add the following line to

QuestionAdmin:

list_filter = ['pub_date']

That adds a “Filter” sidebar that lets people filter the change list by the

pub_date field:

The type of filter displayed depends on the type of field you’re filtering on.

Because

pub_date is a

DateTimeField, Django

knows to give appropriate filter options: “Any date”, “Today”, “Past 7 days”,

“This month”, “This year”.

This is shaping up well. Let’s add some search capability:

search_fields = ['question_text']

That adds a search box at the top of the change list. When somebody enters

search terms, Django will search the

question_text field. You can use as many

fields as you’d like – although because it uses a

LIKE query behind the

scenes, limiting the number of search fields to a reasonable number will make

it easier for your database to do the search.

Now’s also a good time to note that change lists give you free pagination. The

default is to display 100 items per page.

Change list pagination,

search boxes,

filters,

date-hierarchies, and

column-header-ordering

all work together like you think they should.

Customize the admin look and feel

Clearly, having “Django administration” at the top of each admin page is

ridiculous. It’s just placeholder text.

That’s easy to change, though, using Django’s template system. The Django admin

is powered by Django itself, and its interfaces use Django’s own template

system.

Customizing your project’s templates

Create a

templates directory in your project directory (the one that

contains

manage.py). Templates can live anywhere on your filesystem that

Django can access. (Django runs as whatever user your server runs.) However,

keeping your templates within the project is a good convention to follow.

Open your settings file (

mysite/settings.py, remember) and add a

DIRS option in the

TEMPLATES setting:

mysite/settings.py

TEMPLATES = [

{

'BACKEND': 'django.template.backends.django.DjangoTemplates',

'DIRS': [os.path.join(BASE_DIR, 'templates')],

'APP_DIRS': True,

'OPTIONS': {

'context_processors': [

'django.template.context_processors.debug',

'django.template.context_processors.request',

'django.contrib.auth.context_processors.auth',

'django.contrib.messages.context_processors.messages',

],

},

},

]

DIRS is a list of filesystem directories to check

when loading Django templates; it’s a search path.

Organizing templates

Just like the static files, we could have all our templates together, in

one big templates directory, and it would work perfectly well. However,

templates that belong to a particular application should be placed in that

application’s template directory (e.g. polls/templates) rather than the

project’s (templates). We’ll discuss in more detail in the

reusable apps tutorial why we do this.

Now create a directory called

admin inside

templates, and copy the

template

admin/base_site.html from within the default Django admin

template directory in the source code of Django itself

(

django/contrib/admin/templates) into that directory.

Where are the Django source files?

If you have difficulty finding where the Django source files are located

on your system, run the following command:

$ python -c "import django; print(django.__path__)"

Then, just edit the file and replace

{{ site_header|default:_('Django administration') }} (including the curly

braces) with your own site’s name as you see fit. You should end up with

a section of code like:

{% block branding %}

<h1 id="site-name"><a href="{% url 'admin:index' %}">Polls Administration</a></h1>

{% endblock %}

We use this approach to teach you how to override templates. In an actual

project, you would probably use

the

django.contrib.admin.AdminSite.site_header attribute to more easily

make this particular customization.

This template file contains lots of text like

{% block branding %}

and

{{ title }}. The

{% and

{{ tags are part of Django’s

template language. When Django renders

admin/base_site.html, this

template language will be evaluated to produce the final HTML page, just like

we saw in

Tutorial 3.

Note that any of Django’s default admin templates can be overridden. To

override a template, just do the same thing you did with

base_site.html –

copy it from the default directory into your custom directory, and make

changes.

Customizing your application’s templates

Astute readers will ask: But if DIRS was empty by

default, how was Django finding the default admin templates? The answer is

that, since APP_DIRS is set to True,

Django automatically looks for a templates/ subdirectory within each

application package, for use as a fallback (don’t forget that

django.contrib.admin is an application).

Our poll application is not very complex and doesn’t need custom admin

templates. But if it grew more sophisticated and required modification of

Django’s standard admin templates for some of its functionality, it would be

more sensible to modify the application’s templates, rather than those in the

project. That way, you could include the polls application in any new project

and be assured that it would find the custom templates it needed.

See the template loading documentation for more

information about how Django finds its templates.

Customize the admin index page

On a similar note, you might want to customize the look and feel of the Django

admin index page.

By default, it displays all the apps in INSTALLED_APPS that have been

registered with the admin application, in alphabetical order. You may want to

make significant changes to the layout. After all, the index is probably the

most important page of the admin, and it should be easy to use.

The template to customize is admin/index.html. (Do the same as with

admin/base_site.html in the previous section – copy it from the default

directory to your custom template directory). Edit the file, and you’ll see it

uses a template variable called app_list. That variable contains every

installed Django app. Instead of using that, you can hard-code links to

object-specific admin pages in whatever way you think is best.

Source : https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.10/intro/tutorial07/

This isn’t impressive with only two fields, but for admin forms with dozens

of fields, choosing an intuitive order is an important usability detail.

This isn’t impressive with only two fields, but for admin forms with dozens

of fields, choosing an intuitive order is an important usability detail.

In that form, the “Question” field is a select box containing every question in the

database. Django knows that a

In that form, the “Question” field is a select box containing every question in the

database. Django knows that a  It works like this: There are three slots for related Choices – as specified

by

It works like this: There are three slots for related Choices – as specified

by  One small problem, though. It takes a lot of screen space to display all the

fields for entering related

One small problem, though. It takes a lot of screen space to display all the

fields for entering related  Note that there is an extra “Delete?” column that allows removing rows added

using the “Add Another Choice” button and rows that have already been saved.

Note that there is an extra “Delete?” column that allows removing rows added

using the “Add Another Choice” button and rows that have already been saved. By default, Django displays the

By default, Django displays the  You can click on the column headers to sort by those values – except in the

case of the

You can click on the column headers to sort by those values – except in the

case of the  The type of filter displayed depends on the type of field you’re filtering on.

Because

The type of filter displayed depends on the type of field you’re filtering on.

Because